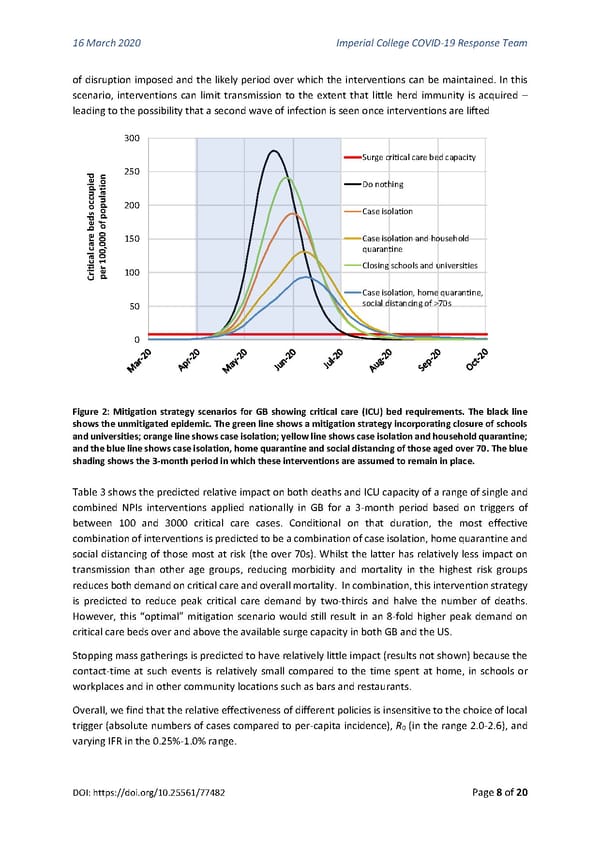

16 March 2020 Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team of disruption imposed and the likely period over which the interventions can be maintained. In this scenario, interventions can limit transmission to the extent that little herd immunity is acquired – leading to the possibility that a second wave of infection is seen once interventions are lifted 300 Surge critical care bed capacity dieon 250 ilat Do nothing occup oup200 sedf p Case isolation be 0 o car0,0 150 Case isolation and household cal100 quarantine iriter 100 Closing schools and universities C p Case isolation, home quarantine, 50 social distancing of >70s 0 Figure 2: Mitigation strategy scenarios for GB showing critical care (ICU) bed requirements. The black line shows the unmitigated epidemic. The green line shows a mitigation strategy incorporating closure of schools and universities; orange line shows case isolation; yellow line shows case isolation and household quarantine; and the blue line shows case isolation, home quarantine and social distancing of those aged over 70. The blue shading shows the 3-month period in which these interventions are assumed to remain in place. Table 3 shows the predicted relative impact on both deaths and ICU capacity of a range of single and combined NPIs interventions applied nationally in GB for a 3-month period based on triggers of between 100 and 3000 critical care cases. Conditional on that duration, the most effective combination of interventions is predicted to be a combination of case isolation, home quarantine and social distancing of those most at risk (the over 70s). Whilst the latter has relatively less impact on transmission than other age groups, reducing morbidity and mortality in the highest risk groups reduces both demand on critical care and overall mortality. In combination, this intervention strategy is predicted to reduce peak critical care demand by two-thirds and halve the number of deaths. However, this “optimal” mitigation scenario would still result in an 8-fold higher peak demand on critical care beds over and above the available surge capacity in both GB and the US. Stopping mass gatherings is predicted to have relatively little impact (results not shown) because the contact-time at such events is relatively small compared to the time spent at home, in schools or workplaces and in other community locations such as bars and restaurants. Overall, we find that the relative effectiveness of different policies is insensitive to the choice of local trigger (absolute numbers of cases compared to per-capita incidence), R (in the range 2.0-2.6), and 0 varying IFR in the 0.25%-1.0% range. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25561/77482 Page 8 of 20

Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand Page 7 Page 9

Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand Page 7 Page 9